Transforming Cultures

theory, method and practice

Peter W Tait (Ed.)

Contents

Forward to this Edition

Preface

Context and background to project and how it fits into the Fundamental Questions Program and Frank Fenner Foundation.

Introduction

The opening chapter draws together the key reflections on theory, methodology and practice.

Summarises the major themes about cultural change.

Context and Summary

Chapter 1

The main themes and lessons

In this chapter we outline the major returns emerging from the Transforming Cultures series. We provide a brief overview of the Transforming Cultures Framework. We the list the major assumptions and values that arose from discussions. Next we summarise what we have learnt about the major processes of transformation, using two different typologies.

Chapter 2

Transformation Literature Review

Places the presentations within the broader context of the culture transformation / change literature.

Literature Review Summary Table

Chapter 3

A framework for change

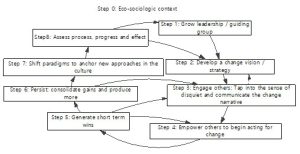

Bob Webb’s Kotter work.

Finally with the outputs from the typologies in Chapter 1 put into the Framework to explain how they might be applied.

Chapter 3 Appendix Cultural Transforming Frameworks and discussion.

Presentations and Commentary

Each chapter comprises the presentation(s) of each Human Ecology Forum session. Following the paper derived from each presentation is a brief editorial commentary linking them into the broader themes of the monograph (cultural transformation) and drawing out the key messages for the transforming culture project.

Chapter 4

Tim Hollo & Aileen Power: Cultural change is essential

How ‘culture’ as art, music, drama etc, is important for changing Culture.

Presentation.

Summary and Commentary.

Chapter 5

Barry Newell: The Transition to a Biosensitive Society

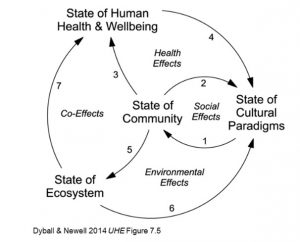

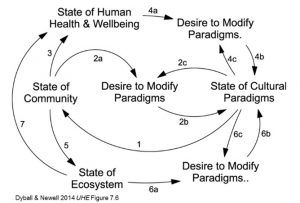

A systems approach to culture change. Transforming Boyden’s biosensitive triangle into a system approach.

Summary and Commentary.

Chapter 6

Tom Faunce: Towards Eco-centric Governance in the Sustainocene with Global Artificial Photosynthesis

Social change depends on having a technological pathway to permit the change. Artificial photosynthesis provides that path.

Summary and Commentary.

Chapter 7

Bob Douglas: Transformational Culture Change

How Castro in Cuba generated a cultural and political transformation.

Paper and Commentary.

Chapter 8

Elizabeth Boulton: Philosophy tackles Climate Change the Hyperobject Narrative

Exploring how the Hyperobject narrative approach might be applied to cultural transformations.

Summary and Commentary.

Chapter 9

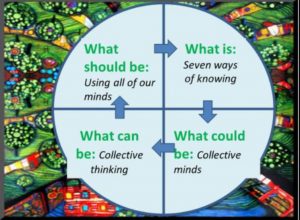

Val Brown & John Harris: Reshaping our minds - parameters of Transformation

How using a thinking methodology, the seven ways of knowing, can help facilitate transformations.

Summary and Commentary.

Chapter 10

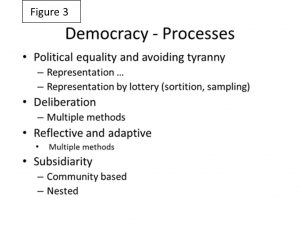

Kevin Thomson: A Parliamentary look at Cultural Transformation

Parliaments are working badly. Specific practical reforms are needed to build them as a means for change.

Summary and Commentary.

Chapter 11

Mark Stafford Smith: Facing accelerating change - the role of research

Future Earth and the role of research in helping change society - summary.

Chapter 12

Bob Costanza: A theory of Socioecological Systems Change

How can scenario planning help create a new future?

Summary and Commentary.

Chapter 13

Gill King: Using Marketing for transformation

Marketing as a tool for motivating and change to happen.

Summary and Commentary.

Chapter 14

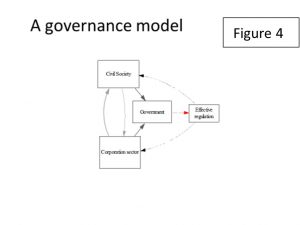

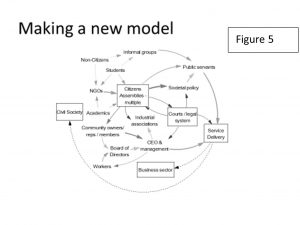

Peter Tait: Governance for the Anthropocene

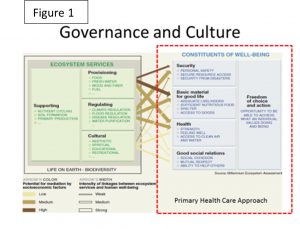

To make the decisions required for transformation to a biosensitive society, we need to understand governance and reform that to achieve the greater outcome.

Chapter 15

Val Brown: Collective Mind - Application to Transforming Cultures

Another look at how we apply seven ways of knowing to help make change.

Chapter 16

Tim Hollo: Music as a path to transformative cultural change.

Music speaks to the soul through the seven ways of knowing.

Chapter 17

Peter Tait: Wresting power transforming governance.

To bring about a cultural transformation, existing power structures which are both culturally determined and determine culture must be challenged and changed.

Chapter 18

Jodie Pipkorn, SEE-Change: Transforming Cultures Case - Transition Towns Canberra.

Looks at how the Transition Town Canberra is building connections to help transform Canberra society; with Commentary.

Chapter 19

Ian Morland: Transforming Cultures - Beginning with Individuals.

A demonstration of engaging people in a narrative; Commentary.

Chapter 20

Richard Denniss: Exercising Power for Cultural Transformation.

Cultural change is a matter of exercising power, But to exercise power for good one needs to consider who is exercising the power to what end; synopsis and commentary.

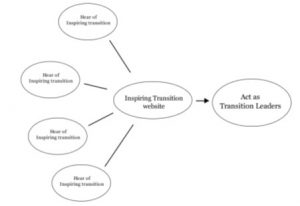

Chapter 21

Andrew Gaines: Communicating to accelerate the Great Transition.

A demonstration of a communications method.

Chapter 22

Trevor Hancock: Public Health in the Anthropocene.

Chapter 23

Lyn Goldsworthy, Frank Fenner Foundation: Biosensitivity - how does this help Transform Cultures

Biosensitivity – part of the new values narrative about what people can do to transform.

Appendices

Appendix 1 HEF Transforming Cultures Series Contributors

Appendix 2 2014 Concluding Workshop Summary Outcomes

Appendix 3 TRANSFORMING Cultures 2015 Opening overview and summary

Appendix 4 Culture definitions

Appendix 5 Further reading on change: These are a few publications that came up or have been discovered in the process of formulating this Transforming cultures series. It is far from a complete or definitive list. I share it for your interest.

Transforming Cultures: theory, methods and practice

Published 2020 by the Frank Fenner Foundation as an electronic book.

Frank Fenner Foundation

PO Box 11

Canberra ACT 2601

Copyright Frank Fenner Foundation, 2020

Republished 2022 in Canberra Alliance for Participatory Democracy Resource Hub.

Peter W Tait (Ed), 2020, Transforming Cultures: theory, methods and practice, Frank Fenner Foundation, Canberra ACT Australia

Citations for each section should acknowledge the presenter/author(s) and title of that section in addition to the above citation.

Front cover art work: Samantha Towers, Auckland, New Zealand/Aoteoroa

Back cover photograph by Peter W Tait, of David Jensz Cultural Fragment, Woden, ACT

Transforming Cultures

In 2022 it appeared that the Frank Fenner Foundation, under whose auspices the original Human Ecology Forum Transforming Cultures series was run, was going to close down and the website version of this series might become unavailable. Therefore the Transforming Cultures e-version was copied across to the Canberra Alliance for Participatory Democracy Resources Hub to preserve it for use into the future.

In this transfer process, the publication was formatted into a webpage style of text with illustrations. Links to the pdfs of the original chapters are given, mainly at the end of each chapter, for downloading and reading offline. In some cases there is no chapter text as such because this was not supplied by the authors; we only have access to their original presentations. In this case, links to these presentations are given.

Many of the presentations are accompanied by a brief summary, synopsis and commentary to draw out importance points for the series. These are usually also put at the end of each chapter.

As new material comes to hand, this is added at the end in the section titled Addenda.

Enjoy

Peter Tait

In the early 1990s, the Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies (CRES[1]) Human Ecology Group’s Fundamental Question program explored how to achieve the cultural transformation, or ‘biorenaissance’, to an ecologically sustainable human society. They produced a book, Our Biosphere under Threat (Boyden, Dovers et al. 1990), and a series of monographs.

The 2014 and 2015 Human Ecology Forum Transforming Cultures theme sought to extend this work by addressing this core question: how might we bring about the necessary cultural transformation to ensure the long term survival of the human species? This is about societal change, that is the mix of individual and systems change needed to transform culture. This series wants to elaborate the theoretical, methodological and practical aspects of a program for cultural change.

The program is grounded on the following assumptions:

- Human activity, grounded in a socio-economic culture that ignores or disrespects the fundamental processes of life and nature, is causing degradation to the natural environment and that this is being detrimental to human prosperity, health and wellbeing.

- Transformation of the current dominant world culture, including its worldview and practices, is imperative to protect human wellbeing.

- This transformation will need to reassert the biophysical realities within which we live and promote a culture which is sensitive to and respects nature and its limits.

- While a rapid transformation is required to protect human civilisation, there is still time to take effective action to minimise disruption to human society.

These assumptions overtly drive and frame the discussion. Further participants recognised that any attempt to change culture is being undertaken by people who are embedded in and part of that culture. Thus cultural change assumes that members of a complex adaptive system can intentionally leverage or tweak elements of the system to attempt change, even while recognising that those people have no inherent capacity to control the system and that any resultant change is unpredictable. It recognises that systems have resilience as well as tipping points.

In the context of Stephen Boyden’s elaboration of the biohistorical phases of humanity (Boyden 2010) (and see Chapter 1), this transition or transformation from the fourth, current high consumption, ecologically unsustainable phase to a fifth phase founded in biosensitivity, based on understanding the human place in nature, in tune with, sensitive to and respectful of the processes of life is called the biorenaissance. This biorenaissance may be termed the “Phase Five Transition”.

The Frank Fenner Foundation (FFF) intends to:

“... convene integrative transdisciplinary discussion and debate on:

- (a) The changes in human activities that will be necessary to achieve the transition to an ecologically sustainable and healthy society

- (b) the changes in societal arrangements ... necessary to bring about ... changes in human activities”

in order to contribute intellectually to the Phase Five Transition. This monograph will contribute to these objectives.

The question and more questions

The major question for this project was how might we bring about the necessary cultural transformation to ensure the long term survival of the human species? This recognises culture as the ‘operating system’ for a society. Sub-questions might include: what will an ecologically sustainable society look like; what aspects of culture need to change to allow that to emerge; how would such change be achieved; what are likely barriers and how can they be circumvented?

As the series progressed, further questions arose and were added:

- What is culture?

- How do individual / personal changes translate up to societal change? Or can they?

- Do we know how to carry out designed, deliberative societal changes across all sectors of society, from within that society?

This monograph

Input from a diverse set of disciplines was sought for each’s contribution to answering these questions. I note the limitation of the absence of input from political science, sociology, history and social anthropology, all of whom may have brought added insights to the series.

The opening first chapter draws together the key reflections on theory, methodology and practice from the presentations. The second chapter puts the themes and lessons from this series into context of a review of the literature on cultural and social change. The third chapter presents a model for change. The presentations which were made to the seminar series follow. They keep the presenter’s style and format to lend authenticity. Some are adapted from documents; others are PowerPoint Presentations. Each is followed by a brief editorial commentary linking them into the broader themes of the monograph and drawing out the key messages for the transforming culture project. It recommends further relevant action.

References

Boyden, S. (2010). Our Place in Nature: past present and future. Canberra, ACT, Australia, Nature and Society Forum Inc.

Boyden, S. V., S. Dovers and M. Shirlow (1990). "Our biosphere under threat."

[1] now the Fenner School for Environment and Society at ANU

Introduction: Transforming Culture: to what and how?

Peter Tait

This Human Ecology Forum 2014 and 2015 Seminar Series wants to elaborate the theoretical, methodological and practical aspects of a program for change. To this end, change theory (there are many formulations of this; for one method see http://www.theoryofchange.org/what-is-theory-of-change/how-does-theory-of-change-work/#6 ) advises a sequence that answers these questions:

- What do we want – what does it look like and how might it work?

- Why do we want this?

- What specifically needs to change in the current system to get us there?

- How do we make those changes: at various levels?

- What will help make those changes?

- What blockages/ barriers are likely to emerge and how can we get around them.

This paper will explore these questions briefly to give some background to the seminar series.

So 1. What do we want?

Our purpose is to bring about a Biosensitive (ecosystem respecting) and therefore Ecologically-Sustainable society.

Stephen Boyden’s term biosensitivity (Boyden 2004) refers to an understanding of the place of humans in the environment that is truly in tune with, sensitive to and respectful of the processes of life; an understanding which can therefore bring clearer insights and strategic guidance to the urgent local and global task of reversing humankind’s excessive pressures on nature’s systems. Biosensitivity provides a lens through which to assess current and future human development proposals. The ‘life’ focus means that both the natural environment including other species and the physiochemical systems of the ecosystem and human societal systems (including the built environment) are respected. Consequently a biosensitive society will result in healthy biosphere supporting healthy people in a healthy society.

Ecological sustainability has these components (drawn from multiple sources):

- It operates within the limitations of the Earth’s biophysical systems

- It recognises and acknowledges the links between human societal behaviours and the effects on the natural world

- It recognises that the interests of non-human species and future generations need to be taken into account in the present

- It promotes the links between a just and equitable human society and respect for Earth’s biophysical systems/ Nature.

Both terms are complementary, putting the focus on slightly different aspects, but united in their view that humanity sits within a greater whole – the biophysical systems of planet Earth. Biosensitivity focusses on how humans regard the living, biological systems of the planet while ecological focuses on the interaction between living things and between them and the physical world. In some respects, Tony McMichael caught the essence in describing biosensitivity as a pre-requisite for ecological sustainability. One is an input state, and the other the outcome.

Project participants may seek to explore what a society operating within these sets of principles might look like in more detail. Readers of the magazine Solutions would remember several articles that explore this (http://www.thesolutionsjournal.com/ ). But what are the social, political and economic institutions and arrangements of such a society? What would it be like to live in? How would it feel?

- Why transform?

To ensure human wellbeing and health by conserving human civilisation in the immediate future, and ultimately ensure the survival of the species Homo sapiens. The reasons for this are spelt out in the assumptions listed above. Put the other way, the present and future wellbeing (that is the health, security, political freedoms and material prosperity) of humanity is being threatened by the current disregard of the biophysical realities by the practices of the dominant socioeconomic system. These practices are defined by culture.

Transformation is a term with multiple meanings. I use it here to mean a shift in the worldviews, governance and socio-economic practices within human systems to a significantly different state than they are now (see discussion in UKCIP report (Lonsdale et al 2015)).

- Why culture?

Again culture carries multiple meanings. It embodies worldviews, beliefs and assumptions, practices of thinking and living, and the ways these are communicated through the ‘arts’ (stories and songs, literature, theatre, music, art) and cuisine of the particular society of which it is a part. In this discussion by culture I mean the default operating system for a particular human society. In saying this, I recognise that there is within societies a dominant culture, and that other non-dominant sub-cultures exist, that may, or may not, align to some extent with this dominant cultural system.

Culture has two aspects: the behavioural which includes social practices, arrangements and institutions, and the beliefs, assumptions or worldview that underlies and explains or justifies behaviour. These are in dynamic equilibrium with each influencing the other.

Therefore to change how humanity operates on the planet, we need to re-design the operating system and reboot the system in that new mode. Both behaviours and beliefs need to change in parallel.

Culture also operates at lesser scales within society; the individual institutions and organisations of the several realms (to borrow Fotopoulos’ model (Fotopoulos 1997)). Realms include the political, economic, ecological, social and personal. Social and personal realms overlap and encompass home life, leisure, the workplace, and so forth. There are also cultural factors relating to societal sectors: energy, habitation, transport, industry, agriculture, etc..

Answering the remaining three questions, specifically how to make change and how specifically to bring about change in this culture, are the focus for the rest of this series. Questions at this level look at what current arrangements particularly needs to change and how.

Cultural Transformation

Stephen Boyden has written, in relation to the role of the Frank Fenner Foundation, that it will convene integrative transdisciplinary discussion and debate on:

(a) The changes in human activities that will be necessary to achieve the transition to an ecologically sustainable and healthy society of the future (e.g. changes in energy use, transportation, food production, forestry practices, manufacturing, consumer behaviour, lifestyles)

(b) the changes in societal arrangements that will be necessary to bring about the necessary changes in human activities (e.g. changes in economic arrangements, the occupational structure of the work force, urban design, government regulations, and educational programs).

This seminar series seeks to explore how this might be done.

Processes of Cultural Transformation

Change requires both motivator and a belief that change can occur. We have a motivator (the concerns outlined in the assumptions and aims in the Introduction), but how to harness this so those in power and our fellow citizens move? More importantly, how can we communicate concern and simultaneously engender hope? Concern or fear without hope stymies change and reinforces both the status quo and black and white thinking.

In changing behaviour, we don’t have to waste effort on changing people’s minds and worldviews, which are generally very resistant to change as they are the emotionally charged basic assumptions and beliefs a person has about the world and how it should work. This set of beliefs constitute a person’s identity, and identity is the most strongly defended psychological construct. We also know that if people are put into a situation of psychological dissonance (where their identity and values conflict with an aspect of their perceived reality,) they will react in one of three ways. Usually they just ignore the dissonance and get on with living. However sometimes if compelled by emotions or arguments, they will change their behaviour, and then change their beliefs retrospectively to justify this behaviour change. This is the basis for motivational interviewing. Occasionally however, if the cause of the dissonance is too threatening, people will deny reality and hold to their belief.

We have historically been wedded to the ‘information deficit model’ theory of change. That is the belief that if people only knew the correct information they will change their behaviour. We now know that this belief is mistaken. Other psychological steps are required. However, information is important for change; it is just not usually sufficient. People require information both about what change is required, why it is needed and how it can come about. Additionally, people need a set of structures and processes that set up the psychological conditions in which behaviour will change.

Change come about because people come to believe that a different way of doing something will be better than what happens at present AND that change is possible AND that the pain of change will be worthwhile. There needs to be acknowledgement of the barriers and ideas for how to get around these. So at a personal level, it is discomfort about the present + hope / vision + practical steps for making change that enables the change to occur.

Reuben Anderson (http://vimeo.com/26943709) outlines Ten Myths of Behaviour Change. His focus is on changing individual’s behaviour to achieve ecologically sustainable societal goals. Distilling this into a series of principles we have, in no particular order:

- Make the wanted option the default option: structures and regulation at a societal level designed so doing the right thing is easy and automatic

- Create new habits; changing behaviour is about changing people’s habits: alert people to new habits, focus attention by: legislation and regulations, incentives, costs, prompts; help people to practice new habits; rely on intrinsic rewards

- Appeal to emotions not intellect: use insightful story telling

- Renormalising: people do what friends and neighbours do. So use social marketing to spread this message and develop social proof for people that this is what is normal

- Design systems for people, according to how our brains actually work, taking limits to cognitive capacity into account

Communicating needs to be undertaken with careful forethought and planning. Again, communicate in a manner and with methods that are going to get your message to the people you intend to receive it. Additionally, there are some critical factors to be born in mind with messaging effectively:

Framing and language show your audience the aspects and meanings of the message you want them to receive: Lakoff (framing)(Lakoff 2006) and Senior (working with people’s own concerns)(Senior 2014) and Jonah Berger (viral stories)(Berger 2013) and others explain in more detail.

Beware reinforcing your opponents message. John Cook & Stephan Lewandowsky in The Debunking Handbook (Cook and Lewandowsky 2011) explain about three ‘backfire effects’:

- familiarity - repetition reinforces belief (‘Goebbelization’)

- overkill - a simple myth is accepted more than a complicated correction

- worldviews - very difficult to change - this change may be traumatic

So, only mention your opponent’s message (briefly in outline) to say it is false then give brief succinct reasons why, and then repeat your message. Keep the correction clear and simple; if necessary provide options for more detailed explanations nearby. Avoid threatening worldviews; work with them by speaking to values and framing acceptably.

So far this discussion of change has focused on individuals. But what about transformation at a societal level? Since culture is the operating system of society, to change how society operates, we need to change culture. What do we know about changing culture? We know about changing people’s behaviour individually; how does this translate to a community level? We know a lot about effective communications. We can use this knowledge to designing a cultural transformation.

References

Berger, J. (2013). Contagious: Why Things Catch On. New York, Simon & Schuster.

Boyden, S. (2004). The Biology of Civilisation: Understanding Human Culture as a Force in Nature. Sydney, University of New South Wales Press.

Cook, J. and S. Lewandowsky. (2011). "The Debunking Handbook." Retrieved 5/3/2014, from http://www.skepticalscience.com/Debunking-Handbook-now-freely-available-download.html.

Fotopoulos, T. (1997). Towards an inclusive democracy: The crisis of the growth economy and the need for a new liberatory project. London, New York, Cassell.

Lakoff, G. (2006). Don’t Think of an Elephant. Melbourne, Scribe Short Books.

Lonsdale K, Pringle P, Turner B. Transformative adaptation: what it is, why it matters & what is needed. Oxford, UK: UK Climate Impacts Programme, University of Oxford; 2015.

Senior, T. (2014) "Climate change and equity: whose language is it anyway?" Inside Story.

Download pdf of Introduction: Transforming Culture: to what and how?

Transforming cultures is a mix of theory of culture, methods of system change and practice of creating attitude and behaviour change.

In this chapter I list the major assumptions and values that arose from discussions. Then, I summarise what we have learnt about the major processes of transformation, using two different typologies to demonstrate differing aspects of cultural transformations.

Finally, to ensure an ethical process occurs, the participants in the wrap up workshop suggested that the founding assumptions, our values and a set of principles to direct the guiding coalition have to be made explicit. Such principles are in a state of evolution but suggestions to date are:

Values and Principles:

- The process of change must be ethical and grounded in a set of values

- Value dissent

- Respect for diversity of knowledge and approach

- Recognise change is an emotional process

- Recognise we are designing influence not change

- Recognition that communication (whatever medium) is an iterative dialogic process

- Be reflective

Assumptions:

- There is an overarching assumption that the continuation of the human species on the planet carries value, as least to humanity.

- At the next level, a meta-purpose of society is the wellbeing of its members and the survival and continuation of the group.

- Human collective behaviour as manifest as culture. The dominant cultural worldview is disrupting the ecological foundations that support human society and the existence of other species.

- Transformation of the current dominant world culture is imperative to ensure human survival and minimise disruption to the ecosystem and other species.

- This transformation will need to reassert the biophysical realities within which we live and promote a culture which is sensitive to and respects nature and its limits.

- There is still time to take effective action to minimise disruption to human society.

- Systems are resilient but adaptable.

- It is possible to attempt a transformation by designing a change that will influence the system

- It is possible to influence complex adaptive systems but not to control the effect.

- While an intent for transformation might be agreed, all other details of all other aspects, even final outcomes, are open to varying degrees of contestation and disagreement, but these are worked out within the larger, collective concordance about intent.

- Human wellbeing and the natural world would be optimal if human societal behaviour was to accede to a set of values including but not limited to: biosensitivity, better resource use, externalities reflected in costing decisions, recognising biophysical realities/limits, in other words having ecological sustainability

Processes of transformation – what have we learnt

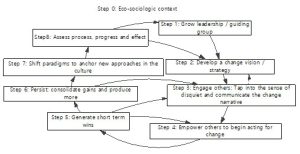

Firstly, in Chapter 3 we outline one possible model of change process. Each step in this framework as a primary task, which in turn can be broken down further into other tasks (see figure 1). This will be discussed later.

We have collected a set of values and principles and clarified our assumptions.

Next, we have accrued a set of recurrent themes that pertain to undertaking cultural change. A couple of different and non-exclusive ways to assemble these are given below to facilitate discussion.

A theory, methodology or practice framework, proposed at the beginning of the Human Ecology Forum theme, provides the first take for reflection.

Theory

- Culture is communication within society and across the generations of a society

- Culture is about exercising power by establishing the operating system for a society. Therefore, it is political, socially constructed and so subject to being changed.

- Cultural transformation as an evolutionary process reveals (unfolds) an approach to systems change that regards influences into the system as selection pressures.

- Recognising culture is a hyperobject (reference Liz Boulton) provides a method for adjusting frames and identities.

- Change requires thinking “outside the box”, envisioning requires us to consider what is needed not what is possible.

- Change involves transgression and subversion leading to disruption to existing power relationships and hence conflict will occur

Methodology

- System models provide a method for understanding and analysing a system, and provide a language to negotiate and share that understanding.

- Scenario planning gives a methodology for envisioning, and testing out, a set of possible futures.

- The collective mind is a methodology for working with groups of people to help them achieve a common purpose. The agreement about the purpose is the collective mind.

Practice

Practice revolves mostly about marketing, which is about communications that draw on and apply research in psychology and neurobiology.

- Stories (narratives) are central to our identity, and for staying in status quo, and equally critical in bring about change. Our stories give us meaning and understanding of the world. New stories that give new meaning, purpose and describe how things might be are needed to replace the current stories and to help forge a new identity. Changing identity is challenging. It requires changing the frames (including the narratives and metaphors) that give us identity, to permit a new identity to emerge. It requires addressing the emotional responses to the change and using the emotions to shift the frames.

- Because words carry multiple meanings, to appeal to the emotions communications need to draw on multiple media: tell stories, dance, sing, play, draw, paint, cartoon and sculpt.

- Applying the seven ways of knowing and the collective mind process for designing intentional influence into a system opens reframings necessary to trigger change.

- Marketing, applying psychological knowledge and theories of change, can be used ethically to guide strategy and tactics to reframe situations and help change individual and group identities to bring about cultural transformation.

- Besides marketing, transgression and subversion leading to disruption to existing power relationships is necessary.

- Technology and infrastructure, the hardware of society, affect the boundaries and abilities for change to occur. Putting effort into changing these adjunct systems can facilitate culture change. Two examples are:

- More generally novel technologies provide means for changing cultural structures; examples the abolition of slavery by machines (industrialised capitalism); creation of capitalism by technologies to better harness energy: developments in wind, water and lastly fossil fuels technology. So in future synthetic photosynthesis may provide opportunity for another change.

- Specifically energy systems are fundamental to both political and literal power within society. Changing the energy system can open opportunity for change in political and economic power. This is particularly relevant for the transition from fossil fuel to renewable energy sources. Additionally efficient use of energy and an overall reduction in the amount of energy used will press for change in cultures, as well as being an outcome of the primary culture change.

- Disruption to existing power relationships will provoke resistance to change and the resultant conflict will need to be managed.

An alternative typology might be:

About culture

- Culture is communication between and across the generations of a society

- Culture is about exercising power by establishing the operating system for a society. Therefore it is political, socially constructed and so subject to being changed.

- Recognising culture as a hyperobject directs attention to transformation as a process of changing frames and identities.

About change

- System models provide a method for understanding and analysing a system, and provide a language to negotiate and share that understanding

- Cultural transformation as an evolutionary process reveals (unfolds) an approach to systems change that regards influences into the system as selection pressures.

- Change requires thinking “outside the box”, envisioning requires us to consider what is needed not what is possible.

- Applying the seven ways of knowing and the collective mind process for designing intentional influence into a system opens reframings necessary to trigger change.

- Change involves transgression and subversion leading to disruption to existing power relationships and hence conflict will occur

- Scenario planning gives a methodology for envisioning, and testing out, a set of possible futures.

- Stories (narratives) are central to our identity, and for staying in status quo, and equally critical in bring about change. Our stories give us meaning and understanding of the world. New stories that give new meaning, purpose and describe how things might be are needed to replace the current stories and to help forge a new identity. Changing identity is challenging. It requires changing the frames (including the narratives and metaphors) that give us identity, to permit a new identity to emerge. It requires addressing the emotional responses to the change and using the emotions to shift the frames.

- Because words carry multiple meanings, to appeal to the emotions communications need to draw on multiple media: tell stories, dance, sing, play, draw, paint, cartoon and sculpt.

- Marketing, applying psychological knowledge and theories of change, can be used ethically to guide strategy and tactics to reframe situations and help change individual and group identities to bring about cultural transformation.

- Besides marketing, transgression and subversion leading to disruption to existing power relationships is necessary.

- Technology and infrastructure, the hardware of society, affect the boundaries and abilities for change to occur. Putting effort into changing these adjunct systems can facilitate culture change. Two examples are:

- More generally novel technologies provide means for changing cultural structures; examples the abolition of slavery by machines (industrialised capitalism); creation of capitalism by technologies to better harness energy: developments in wind, water and lastly fossil fuels technology. So in future synthetic photosynthesis may provide opportunity for another change.

- Specifically energy systems are fundamental to both political and literal power within society. Changing the energy system can open opportunity for change in political and economic power. This is particularly relevant for the transition from fossil fuel to renewable energy sources. Additionally efficient use of energy and an overall reduction in the amount of energy used will press for change in cultures, as well as being an outcome of the primary culture change.

- Disruption to existing power relationships will provoke resistance to change and the resultant conflict will need to be managed.

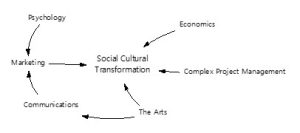

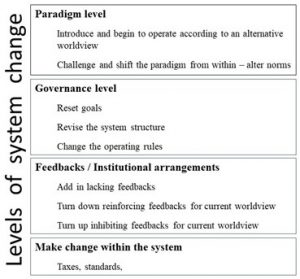

Another way to considering these elements is diagrammatically. This first diagram (Figure 2) summarises the major elements that were identified as helping to drive specifically cultural transformation.

The second (Figure 3) looks at a slightly different set of influences on change.

Finally returning to the Kotter-Webb-Tait framework (Figure 1), I assemble the ideas elaborated above into the framework it provides. I embed the parallel Kotter stage labels Goals, Framing,

Knowledge and Technology, Institutions, Paradigms into the steps of the model since each Kotter stage will have elements of all.

An aside on communications and marketing

The role of communications is relevant to all of the Steps (Adam Ferrier book, The Advertising Effect: How to Change Behaviour, is an invaluable resource). The word marketing as used here, is a communications process that uses a variety of techniques based in the neurocognitive and psychology disciplines to attract, interest and engage people, lead them on the journey to discover what it is that transformation can help them achieve. It talks to people’s emotions at the same time as their reason. Marketing does not have to be advertising, nor manipulative (although it often is used this way). As a communication process it is a tool to help achieve our purpose.

Download a pdf of Chapter 1 Transforming Cultures Key Themes and Lessons

The purpose of this chapter is to place the presentations from the Transforming Cultures series within the context of the broader literature on cultural transformation and change more generally. The literature largely agreed with or added caveats to the viewpoints of the presenters. Where differences with presenters and between different writers were noted in the literature, a more nuanced view of transformation is possible. The Transforming cultures presenters added valuable findings to the sections on Communications/Marketing, Biosensitivity and the Role of the Arts.

Further, this review highlights the interconnection of some of the ideas presented. One cross cutting emergent theme was that transforming cultures is a process of social evolution. Various factors such as leadership and technology could be seen as providing selection pressure within that social evolutionary perspective. The other intercurrent theme is that transformation requires an interplay of individual level and community change happening in parallel.

Methods

Online literature searches were conducted in four databases: ProQuest Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect and Web of Science in April 2018. There were initially 68 records identified through the database search, and a further six records found through referenced works which appeared frequently in the identified literature.

Search terms

| Cultural change | Cultural transformation |

| Social contract theory | Social transformation |

| Environmental policy | Socio-economic change |

Inclusion criteria

| Systems-change approach | Technology and cultural change |

| Resilience | Workplace and organisational change |

| Tipping points | Scenario-planning |

| Nudge theory | Anthropology of social change |

| Public health | Biosensitivity |

Exclusion criteria

| American Medicine | Patient-centred case |

| Indigenous knowledge | Early modern Europe |

| Post-communist | Post-war |

| Film | Global media |

| Sports | Television |

Article inclusion criteria

| Criteria | Application |

| Relevance to topic | Articles must be directly related to the topic; different contexts and scales of cultural transformation are acceptable |

| Peer reviewed | Articles must be peer-reviewed |

| Age of material | Articles must be less than five years old |

| Design of studies | Qualitative studies should be included |

Eligibility

49 articles were assessed for eligibility and selected. Abstracts and conclusions were analysed to rule out articles based on relevance or applicability to the topic.

The review was then narrowed down to 27 articles. Following a systematic reviewing of all relevant articles, a thematic analysis was used to identify overall themes and identify specific examples.

The literature suggested four main topic domains, with a fifth assemblage of factors not fitting clearly into the main four. These are grouped into: resistance to change, community based movements, policy and leadership lead initiatives, non-regulatory approaches and the role of research and scenario planning.

Resistance-to-change factors

There is extensive resistance to change influenced by various factors and, as such, much discussion of how that resistance can be addressed and contested. Power and Hollo view culture as a social construct, and found that because of this, it can be deconstructed and changed; when culture is contested, tensions arise that provide openings for change, and exploiting these openings can lead to rapid change. Lyon and Parkings (2013) agreed with this assessment, stating that culture and cultural change are deeply dependent on existing social structures, and that historical factors and societal traditions are critical to the ability of a community to undergo, adapt to and sustain cultural transformation. While Ekdale et al. (2015) also stated that cultural transformation must be contextualised within the culture being addressed, they found that reactions to change are difficult to predict and depend on compatibility, intricacy and relative advantage. This implies that the situation is more nuanced than Power and Hollo suggested, and it may not be as simple as exploiting certain lead-ins for bringing about change.

Costanza discussed socio-ecological systems change, presenting cultural transformation as an evolutionary process. This allowed them to examine an approach to large-scale systems change which regarded influences into the system as selection pressures. They argued that culture is composed of worldviews, institutions and technologies, which are subject to selection pressure. This is primarily because subcultures within a dominant culture tend to hold and practice different attitudes, values, institutions and technologies; these differences allow a selection process in response to pressures from the biophysical and social world. Messner (2015) held similar views, adding that the increasing debate and discussion on the topic of transforming culture for a lower carbon future, in itself, reflects a shift in values in society. Hansen et al. (2014) further added that rather than traditional values and heritage acting as a barrier, they provide an alternative method of forming cultural change. Ellis (2018), on the other hand, stated that changing the dynamics of social structures is very challenging and achieving a cultural shift would require overcoming substantial technical and empirical challenges on every level. This suggests that the differences in subcultures may both cause cultural transformation to be more challenging as well as enabling openings for change to occur.

Community-based movements

Morland aimed to determine what causes societies and individuals to become more ethical, citing several examples, and determined that morality is key; inspired moral leadership and laws based on ethical principles are what can pave the way for cultural change. This begins with individuals and then extends to community-based scales. Barr and Prillwitz (2014) concurred, stating that widespread behavioural change and transformation, at their core, start at an individual level. Messner (2015) had a similar perspective, stating that gradually changing individual values is what sets the stage for new standards of development. Hartijasti and Toar (2015) further emphasised this through a case study which demonstrated that cultural shifts are much easier to accomplish and sustain at smaller scales and tend to be more effective when implemented as such rather than on larger levels.

Moreover, when considering behavioural change from an organisational planning standpoint, Willis et al. (2016) deliberated that establishing a collaborative workplace culture can make shifts within that culture much easier. Jones and Harris (2014) had similar findings, particularly in terms of the role of social cohesion aiding organisational growth and behavioural development amongst employees. Thus, Brown (2014) found that recognising where the strengths of a community lie in terms of social cohesion is crucial to adapting to and minimising the drawbacks of cultural change.

Pipkorn, in their discussion of transition towns, proposed that the nature of systems is to adjust; if there is enough of a push from a community level, policies, bureaucracy and regulatory structures will change as a result. Additionally, they implied that grassroots movements and governance have a reciprocal relationship, which the literature further verified. Jones et al. (2014) suggested that policies driving cultural change must be ‘coproduced’ with communities and Barr (2014) agreed, stating that the gradual integration of community-led cultural change within policy and research findings is vital. Lewis (2015), however, had an opposite outlook, specifying that the importance of grassroots initiatives is the way in which they allow individuals and societies to adapt to policy change with ease.

Policy and leadership-led initiatives

Tait et al. discussed the importance of dismantling power structures in initiating cultural change. They acknowledged that changing how political power is exercised requires a transformation of governance, but argued that socio-political culture is what will drive this. In particular, communities taking the lead on this transformation is vital to addressing the equity issues which are rampant in power structures. Power determines what is known and what cannot be known, what can be discussed, and what is not even considered. The existing power dynamics within a society are largely culturally determined, but they also play a key role in determining culture. The literature supports this, with considerable discussion on community resilience and social cohesion as a means through which policy can be adapted by communities to encourage cultural transformations (Brown 2014). In addition, Jones et al. (2013) also found that existing political climates and policy instruments determine and shape the effectiveness of future policies, adding that considering the context of different regions when applying policies is critical to their success. This links to Constanza’s evolutionary view of change, in that existing political climates and policy help select the direction of change.

Correspondingly, Thomson discussed similar themes from a parliamentary standpoint, suggesting that the current system of governance is failing primarily due to the focus on neoliberal culture and economic growth rather than the health and wellbeing of citizens. They compared Australia and countries with similar governance to Scandinavian countries, which follow more pragmatic models of governance and, as a result, have positive social and economic outcomes and strong public support. Thompson identified specific foci for parliamentary process reform in starting cultural change: restricting campaign financing, continuous open disclosure of donations, limits to political advertising, and transparency of all government reports and public money decisions. Sabadie (2014) supported this perspective, stating that the best outcome would require a combination of policy, social innovation and community-based movements. Aside from this, Thomson’s findings were largely new to the discussion of cultural transformation, providing a unique, active member of parliament perspective going forward.

Douglas stressed the importance of leadership and clearly enunciated vision in implementing policies for cultural change, citing 1950s Cuba as an example of rapid transformation through visionary leadership and concurrent strong policies. They suggested that growing inequality in Australia is perhaps a reflection of a corrupt government, which would be a possible trigger for citizens to unite against them and elect a new government. Once in power, Douglas suggested, the new leadership would have to rapidly implement change. Further, there was discussion of the need to establish a Public Interest Council with sufficient resources to propagandise society and government and to advocate and communicate the current situation and new vision. These views were largely supported by literature in the field of employment relations and organisational change. Hartijasti and Toar (2015) stated that managerial aptitudes are key to social change, while Jones and Harris (2014) specified the importance of policies for cultural change being disciplined and structured, with strong leadership. Willis et al. (2016) added that leadership must consider context and regular performance evaluations and motivational management styles provide a foundation for adaptation. In terms of policy, this could translate to government transparency, monitoring and regulation.

Furthermore, Denniss determined methods through which power could be exercised and maintained through existing power systems to bring about cultural change. They suggested that framing policy issues, such as climate change governance, should be done in a manner which is favourable to voters; that is, by promising what they want to happen immediately after the primary goal is achieved. Further, Denniss stated that contesting a political opponent’s view is critical, but framing it as poor policy rather than intentional deceit is key to maintaining positive reinforcement, in the manner of nudge theory. Accumulating political capital on any issues and using it to the advantage of a specific agenda was another recommendation offered here, with Denniss citing John Howard’s use of gun control following the Port Arthur massacre to introduce a GST. Calabrese and Cohen (2013) had similar findings through a study of employment relations, affirming that positive and optimistic methods of leadership allowed employee perspectives to shift, thus creating a constructive work environment where employees felt safe and healthy, with plenty of room to grow. However, Milbourne and Cushman (2015) disputed this, maintaining that the complexity of culture and the diversity of individual views towards social change have limited solutions and are difficult to predict. Barr and Prillwitz (2014) were equally critical, questioning the likelihood and effectiveness of nudge theory in shaping choice architecture, particularly in long-term scenarios. Instead, they suggested that regulatory and non-regulatory approaches to implementing cultural change should be implemented in tandem. This confirms a view that a single influence for change is less likely to succeed than several influencers working together.

Non-regulatory approaches

- Technology

Faunce noted that technology is a possible pathway to eco-centric governance, arguing that corporations have constructed our culture in a manner which advances their own agendas. Having a technological pathway, they argue, would permit social change. For instance, artificial photosynthesis takes the capacity to generate energy away from corporations by decentralising energy production, and in doing so provides abundant energy in a sustainable manner. The use of this technology would support the development of local and democratic energy governance while enabling the economy to flourish, thus freeing people up to spend more time on meaningful cultural activities which are unrelated to work. Messner (2015) added that discourse around cultural transformation for a more sustainable future is crucial to bringing about economic and technological transformation, implying that these goals are heavily linked to culture.

In addition, Hepp et al. (2015) found that, in recent years, digital media has been the cause of several significant cultural shifts; examples include education becoming increasingly open-access and affordable, influencing social structures and organisations, and directly and indirectly influencing audience perceptions of various issues. However, Sabadie (2014) disagreed, arguing that although technology can help enhance cultural change, as seen with the Arab Spring, it cannot sufficiently act as the primary tool. Ekdale et al. (2015) agreed, adding that change does not occur in isolation, and it can be twofold. They cited the journalism industry as an example, acknowledging the new voices entering the field and changing how reporting occurs as a result of technology and social media, with the caveat that this change has substantially affected the relationship between journalists and readers (Ekdale et al. 2015).

Costanza, on the other hand, discussed the link between technological advancement and shifts in attitudes, citing new technologies as a tool to change perceptions directly. Kral (2014) stated that the evolution of communication technologies has provided a way to enhance and change identities and perceptions, particularly within youth culture, as social interactions have greatly transformed. Linking back to organisational culture, Camisón and López (2014) discovered, through a survey of numerous industrial firms, that advancements in technology provided managers with a greater capacity to lead, and employees with a stronger ability to adapt. Hansen et al. (2014), however, cautioned that developing countries are likely to be more resistant to cultural change through forms of technological advancements.

On balance technological innovations might be a trigger for cultural change (think mobile phones) but are not of themselves sufficient. Nor does introducing a technology direct cultural transformation in any particular way; in an evolutionary sense it is only a selection pressure.

- Communications/marketing

Power and Hollo discussed the power of narratives in shaping culture; stories create our ‘reality’ and maintain societal norms. Therefore, new stories have the ability to create a new reality. King argued for the use of marketing expertise, grounded in psychological knowledge, as a pathway for cultural change. Marketing techniques can be employed to reframe situations and motivate individual behaviour. Unlike previous cultural transformations that were in the midst of major historical or technological shifts the current situation requires a new context for change, and marketing can lead the way. King noted that any marketing tactics used must be employed ethically. This perspective ties into Power and Hollo’s suggestions for shifting narratives, and provides a way forward. Botta (2016) agreed with this point of view, describing communication as a valuable tool which can be a means of encouraging social innovation. However, they noted that public and financial support is necessary for any initiative to shape culture. Although communication is valuable for shifting public perceptions, it is far more challenging to garner financial support.

Gaines noted the importance of communication in terms of inspiring and motivating change. Affecting people’s worldviews in a healthy way is challenging but also an influential leverage point. Gaines described the two main aspects to improve in this regard: improving people’s frameworks for making sense of things and improving their way of acting in the world. They also stated that those in leadership roles within educational and organisational structures can shift their institutional cultures through this method. Hacker (2015) agreed, citing extrinsic motivational tactics as a key point for inspiring cultural change in structured settings. Hartijasti and Toar (2015) also found that positive reinforcement and encouraging outlooks make cultural shifts more likely to be effective and resilient.

- Biosensitivity

There was much discussion of transitioning to a biosensitive society by reframing the cultural issues with which we are currently dealing. Newell determined that understanding the world and cultural behaviours are core aspects of planning change in any system. Goldsworthy noted several barriers to biosensitivity within our current culture, including: the lack of understanding of how interconnected human health is with planetary health; the operation of societies without considering the extent of our impact and limits of ecosystems, and the prevailing view that sustainability is largely impractical. To address this, Goldsworthy suggested, it is crucial to establish a clear and shared vision of the desired outcome towards which we must head. This vision must captivate and motivate communities by activating key human qualities such as our capacity for empathy, compassion and collaboration. Boyden added that to avert the current socio-economic paradigm which is heading in the direction of causing irrevocable damage to the environment, bio-understanding must be created through communities and political leadership. Timko (2013) also stated that a cultural transformation for a sustainable and resilient future requires a shift towards bio-understanding. These considerations added valuable insights into the discourse on cultural change as there was previously very limited academic research on biosensitivity.

Along a similar vein, Hancock proposed the reframing of environmental issues as public health issues as a means to garner backing, funding and societal support. This would provide a valuable pathway for informing communities of the adverse impacts of climate change and establish a deeper understanding of how planetary health affects human health. Hancock suggested documenting the potential health impacts of atmospheric change, pollution, biodiversity loss and resource depletion and proposing an action agenda for public health. These shifts would reduce the vulnerability of those dependent on certain ecosystems and increase their capacity for resilience and adaptation. Lewis and Townsend (2015) also found that establishing a collective awareness of environmental effects on public health would lead to humans developing a more harmonious relationship with nature.

- Role of the Arts

Hollo discussed the unlikelihood of addressing the effects of climate change within the confines of our existing socio-political culture. Key to changing that culture, Hollo argued, is music; music has been pivotal in bridging racial divisions across North America and Britain, and musicians play a critical role as cultural influencers. They also cited lessons from history showing that cultural change is unlikely to occur without such influential cultural processes at play, and artists play a pivotal role. Boulton had similar claims of the power of philosophy. They argued that it allows our narratives to shift by changing ideas about human agency; we have influence but not control. This encourages new questions and, as such, narratives about our identities and roles on the planet to emerge, paving the way for creating a new future. Discussion of these factors was heavily limited, but scholars such as Serra et al. (2017) had corresponding discoveries about the role of the arts; they stated that the use of art for political change and activism enables us to reach new people and express challenging ideas clearly. Such methods are valuable for encouraging cultural shifts among communities.

The role of research and scenario-planning

Stafford Smith identified the role of research in accelerating change, finding that research can help transformation by seeking unanswered questions and providing a framework for designing and planning change. This involves: giving information – however incomplete – to assist with managing uncertainty; providing a compass to help people navigate the chaos and fear that comes alongside large-scale change and uncertainty, and monitoring progress along the journey and advising course corrections. This specific framework is new to the world of research assisting cultural transformation, but there is academic merit to the general idea. Ossewaarde (2017) found that research studies around scenario-planning would contribute to improved understanding of group-culture, particularly in an organisational context, and that this could be used to influence cultural change and shift intrinsic beliefs. Thus, research undeniably plays an important role in encouraging social change.

Likewise, Costanza described scenario-planning as a methodology for envisioning and testing out a set of possible futures. Benefits of this framework included presenting real scenarios to people who may be unsure of why a cultural change would be necessary in the first place. In addition, it would allow people to practice different cultural variations to see which ones would be more effective in adapting to and creating a better future. Bennett et al. (2016) conducted case studies of community-based scenario-planning which had comparable results; participants found the process to be productive and enjoyable, and a major takeaway was that scenario-planning is an effective tool for adaptation research. However, caveats included that the sample sizes were relatively small and larger experiments may be more complex and have different results. Nonetheless, Bennett et al. (2016) maintained that implementing scenario-planning in cultural change research is helpful and noted that more frequent applications of scenario-planning may promise more effective learning, innovation and action.

Chapter 2 Transforming Cultures Literature Summary Table

| Citation | Methodology/Limitations | Outputs | Key findng |

| Barr S, Prillwitz J. A smarter choice? Exploring the behaviour change agenda for environmentally sustainable mobility. Environ Plann C Gov Policy. 2014 Jan;32(1):1-19. | Review of sustainable mobility and behavioural change policies in the UK | · Shaping choice architecture through initiatives such as nudge theory is unlikely to be effective and sustainable in the long-term

· Widespread behavioural change and transformation starts at an individual level · Regulatory and non-regulatory approaches are unlikely to work in isolation; they need to be implemented in tandem |

Individual focus.

Combine regulatory and non-regulatory approaches. |

| Barr S. Practicing the cultural green economy: where now for environmental social science? Hum Geogr. 2014;96(3):231-243. | Policy discussion of barriers to change | · A cultural transformation can only be achieved through community engagement and gradual integration with policy and research findings

· This needs to start at an individual level |

Individual focus generalising to community change. |

| Bennett NJ, Kadfak A, Dearden P. Community-based scenario planning: a process for vulnerability analysis and adaptation planning to social–ecological change in coastal communities. Environ Dev Sustain. 2016;18:1771-1799. | Case studies of community-based scenario planning | · Community participants found that the scenario planning process was productive and enjoyable

· While scenario planning is an effective tool for adaptation, there are many considerations outside of the scope of these case studies that would improve future implementation processes · Frequent applications of such processes might pave the way for more effective learning, innovation and action |

Scenario planning a useful methodology. |

| Botta M. Evolution of the slow living concept within the models of sustainable communities. Futures. 2016 Jan;80:3-16. | Comparison of case studies | · Public and financial support are necessary

· It can be a means of encourage social innovation in spirituality and wellbeing |

Public and financial support necessary. |

| Brown K. Global environmental change I: A social turn for resilience? Prog Hum Geogr. 2014;38(1):107-117. | Anthropological review of resilience, policy and economic intervention | · Community resilience is a means through which policy can be applied to encouraging cultural transformations

· Recognising the strengths of a community in specific areas is the key to planning for, adapting to and minimising the impacts of a cultural transformation |

Recognising community strengths key to cultural transformation.

|

| Calabrese R, Cohen E. An appreciative inquiry into an urban drug court: cultural transformation. Qual Rep. 2013 Jul;18(2):1-14. | Inquiry into organisational culture and workplace relations

Limitations: small sample size |

· Shifting leadership to a positive and optimistic stance shifted the perspectives of employees

· This created a constructive work environment and building a safe and healthy space for learning and growth |

Positive and optimistic leadership helpful. |

| Camisón C, Villar-López A. Organizational innovation as an enabler of technological innovation capabilities and firm performance. J Bus Res. 2014 Jan;67:2891-2902. | Resource-based view theoretical framework, survey of 144 industrial firms in Spain

Limitations: skewed timeline, complex subject |

· Technological innovation greatly aids organisational changes and shifts in employer-employee relationships

· Provided managers with greater capacity to lead, allowing employees to adapt with ease |

Technological innovation aids organisational changes |

| Ekdale B, Singer JB, Tully M, Harmsen S. Making change: diffusion of technological, relational, and cultural Innovation in the newsroom. J Mass Commun Q. 2015;92(4):938-958. | Case study | · Change does not occur in isolation; it can be twofold. For instance, social media technologies have shifted the journalism industry and how reporting occurs, but also the relationship between journalists and the community

· This has also allowed other voices to enter the field of reporting, which has seen mixed responses from society · Resistance to change is natural and reactions are difficult to predict, but they hinge on compatibility, complexity and relative advantage · Any cultural transformation has to be contextualised within the culture it is addressing |

Technologies shift behaviours and relationships.

Culture change is contexted in the culture it occurs in. |

| Ellis EC, Magliocca NR, Stevens CJ, Fuller DQ. Evolving the anthropocene: linking multi-level selection with long-term social–ecological change. Sustain Sci. 2018 Jan;13:119-128. | Agent-based virtual laboratory (AVBL) approach | · It is very challenging to change the formation and dynamics of social structures, which is key to social transformation

· Achieving a cultural shift requires overcoming significant technical and empirical challenges |

Form and dynamics of social structures resist change. |

| Hacker KS. Leading cultural transformation. J Qual Part. 2015 Jan;37(4):13-16. | Review of organisational systems | · Vocational skills training, extrinsic motivation and regular performance evaluation pave the way for cultural change in structured organisations | Training, extrinsic motivators and performance evaluation help change. |

| Hansen N, Postmes T, Tovote KA, Bos A. How modernization instigates social change: laptop usage as a driver of cultural value change and gender equality in a developing country. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2014;45(8):1229-1248. | Longitudinal field experiment | · Advancements in technology enable a dual focus on individual improvement, through self-development and achievement, and communitarianism, through encouraging benevolence and care for others.

· Traditional values and heritage play a large role in social transformation; rather than act as a barrier, they require an alternative method of forming cultural change · Less economically developed communities are more resistant to cultural change via technology |

Technology may help change values.

Values and heritage require attention in changing culture. |

| Hartijasti Y, Toar GH. Assessing cultural transformation from local to global company: evidence from Indonesian PR company. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015 Jan;172:177-183. | Case study

Limitations: only studied one firm |

· Cultural shifts are easier to implement and sustain at smaller scales; this case study demonstrated that it worked at a local level but was much more difficult at a global scale

· Managerial competencies are vital in shaping social change · A positive environment makes the shift more likely to be efficient and resilient |

Local scale change easier to implement than global.

Leadership vital. |

| Hepp A, Hjarvard S, Lundby K. Mediatization: theorizing the interplay between media, culture and society. Media Cult Soc. 2015;37(2):314-324. | Systematic review of mediatisation literature methodology | · Digital media has been the cause of substantial cultural shifts in recent years

· Education has become increasingly open-access · Media both directly and casually influences audience perceptions of various issues · It influences social structures and organisations |

Media technology and use influences social structures. |

| Jones M, Harris A. Principals leading successful organisational change: building social capital through disciplined professional collaboration. JOCM. 2014;27(3):473-485. | Systematic review of cross-cultural organisational change literature | · Collaborative practices and social cohesion can help organisations grow and develop new behaviours

· It must be disciplined and structured · Leadership is key |

Disciplined, structured collaborative practice help develop new behaviours.

Leadership is key |

| Jones R, Pykett J, Whitehead M. Behaviour change policies in the UK: an anthropological perspective. Geoforum. 2013 May;48:33-41. | Ethnographic case study | · It is possible for the state to encourage behaviour change policies on an individual and subsequently group level through nudging

· Barriers to communication and implementation between the state and society must be considered · People are diverse, which presents challenges on how best to encourage cultural shifts · The state operates at various levels and it is unclear as to whether local, regional or national intervention, or some combination, would be most effective |

Population diversity is one factor to accommodate in change strategies.

Combinations of strategies across societal scales are most effective. |

| Jones R, Pykett J, Whitehead M. The geographies of policy translation: how nudge became the default policy option. Environ Plann C Gov Policy. 2014;32:54-69. | Review of policy transition in the UK | · Social change policies should be ‘coproduced’ with the community

· Existing policy and political climates determine how effective any new policies would be · The process of spatial transition of policies is vital to make them more palatable across different regions |

Social change policies should be ‘coproduced’ with the community. |

| Kral I. Shifting perceptions, shifting identities: communication technologies and the altered social, cultural and linguistic ecology in a remote indigenous context. TAJA. 2014;25:171-189. | Review of behavioural and technological data | · The evolution of communication technologies has provided a way to enhance and change perceptions and identities

· This has enabled Indigenous youth culture to change significantly, particularly in terms of communication styles and social interaction |

Technologies is a factor. |

| Lewis M, Townsend M. ‘Ecological embeddedness’ and its public health implications: findings from an exploratory study. EcoHealth. 2015;12:244-252. | Qualitative study of six individuals’ perceptions and experiences

Limitations: small sample size, not easily quantifiable |

· Humans need to collectively develop awareness of our inextricable links with nature, particularly the effects of this on public health

· This understanding will lead to a more harmonious relationship with the ecosystem |

Change in narrative and values focus important. |

| Lewis T. ‘One city block at a time’: researching and cultivating green transformations. Int J Cult Stud. 2015;18(3):347-363. | Combined media methods: video-ethnography, photography | · Grassroots initiatives are key to a cultural focus on sustainable transformation

· Community groups and neighbourhood initiatives allow individuals to adapt to policies with ease |

Grassroots initiatives key. |

| Lyon C, Parkins JR. Toward a social theory of resilience: social systems, cultural systems, and collective action in transitioning forest-based communities. Rural Sociol. 2013;78(4):528-549. | Ethnographic case study of forest-dependent communities | · Cultural change is heavily dependent on existing social structures

· The ability of a community to adapt to and sustain social change relies on historical factors and cultural traditions |

Culture change depends on existing social structures shaped by history and traditions. |

| Messner D. A social contract for low carbon and sustainable development: reflections on non-linear dynamics of social realignments and technological innovations in transformation processes. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2015 Jun;98(1):260-270. | Review of social contract theory in low carbon transitions | · Discourse regarding cultural transformation for a sustainable future serve as the cognitive and normative innovations to pave the way towards economic and technological transformation

· The increasing debate and discussion on this topic reflects a shift in values in society · These changes in individual values as well as sustainability being incorporated into many corporate social responsibility policies for multinational corporations will soon be the new standards for successful development |

Changing discourse helps shift individuals’ values and behaviour leading to societal value change and cultural transformation. |

| Milbourne L, Cushman M. Complying, transforming or resisting in the new austerity? Realigning social welfare and independent action among English voluntary organisations. Jnl Soc Pol. 2015;44(3):463-485. | Review of institutional isomorphism and governmentality theories | · Social cohesion and policy provide valuable frameworks for monitoring changes in organisations and help with the transitioning process

· However, there are limited solutions for the complexity of culture and the varying individual responses towards social change |

Frameworks for monitoring change help transitions. |

| Ossewaarde M. Unmasking scenario planning: the colonization of the future in the ‘Local Governments of the Future’ program. Futures. 2017 Oct;93:80-88. | Discussion of the transformation of the social care sector in the Netherlands | · Research studies around scenario planning can be used to influence cultural change and shift deeply-held beliefs which govern organisational reasoning

· Scenario planning is a highly feasible and effective tool for cultural change |

Scenario planning is a highly feasible and effective tool for cultural change. |

| Sabadie JA. Technological innovation, human capital and social change for sustainability. Lessons learnt from the industrial technologies theme of the EU's research framework programme. Sci Total Environ. 2014;481:668-673. | Review of the implementation and effectiveness of the EU’s Research and Innovation Framework programmes in the field of industrial technologies and its effect on sustainable development | · Human capital in terms of educated citizens is the EU’s greatest asset to a resilient and sustainable future

· Technology and digital media are not the key to cultural transformation but can help enhance it; for instance, the Arab Spring · A combination of community initiatives, social innovation and policy would provide the best outcome |

A combination of community initiatives, social and technological innovation and policy provide the best cultural transformation. |

| Serra V, Enríquez ME, Johnson R. Envisioning change through art: funding feminist artivists for social change. Development. 2017;60:108-113. | Review of feminism activism through arts on a global scale and its effects on policy | · Through the use of parody, humour and beauty, art can help communicate difficult ideas which challenge our worldviews

· Using art for political activism can reach new people in various ways · Art holds value for encouraging cultural change |

Art holds value for encouraging cultural change. |

| Timko M. Biophilic transformation of culture from the point of view of psychology of environmental problems (from cognitive psychology to gestalt theory). Hum Affairs. 2013;23:528-541. | Consideration of how anti-naturalism, gestalt theory and cognitive dissonance affect cultural perception and transformation | · A social transformation towards a sustainable future requires a cultural shift towards biophilic living and adaptation to accepting nature | Values reflected in narratives encourage cultural change. |